Designing Governments: Accessibility and possibility.

Anyone who’s ever tried to understand a piece of “government communication,” or fill out a government form, knows the struggle: antiquated processes are combined with vague and confusing language, leaving you feeling either dumb or confused…or some combination of both. Important information, like directions or processes, are difficult to understand, help is hard to find, and the communication itself is slow to get where it needs to.

But why do governmental documents top the list for “what not to do” when it comes to design and communication? Is it a lack of money? Is it a result of the complexity of laws and regulations?

Or is it, in fact, the lack of communication and design experts in the Oval Office and state buildings around the world?

Design can help make information more accessible.

The users and consumers of government products and services are a diverse set of citizens. Because of the diversity of audiences ranging from age and gender to socioeconomic status and native languages, the design of government messages and processes must accommodate a lot of people. But the problem is that right now, it doesn’t seem to be effective for any of us.

As governments around the world try to get the word out about the changing rules around the ever-spreading Coronavirus, their lack of experience in effective communication and user-centric design becomes even more apparent. Effectiveness and speed are critical, and especially in times of crisis, slow and cumbersome isn’t really acceptable.

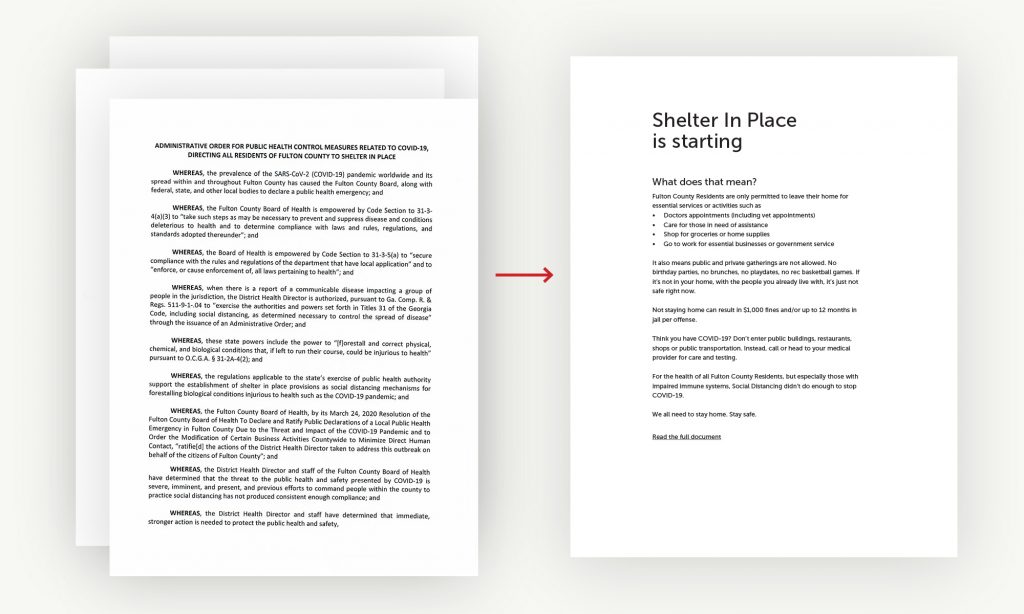

A few weeks ago, the city of Atlanta put out a statement about “our” shelter-in-place order, and shared an Instagram post that linked to the order. Logical so far. But once I clicked on the link, I was directed to a three-page document that used legal jargon to explain what “shelter-in-place” really means. After reading it, I wasn’t sure I understood the order any better than before. In fact, it was so complex and confusing, it may have made things worse.

I understand that legal language is needed, especially when navigating the complex political system and myriad of factors at play. But I can’t help but wonder if there is a better, more effective way to communicate to the general public. The document was neither easy to understand nor quick to read, and likely should have been kept for a more formal audience, with a different type of communication crafted for the general Atlanta population. What if the four-page document was simplified? What if four-pages turned into a one-page document with clear instructions?

What if a three-page document of legal jargon became a one-page document explaining key takeaways?

We talk a lot about audience segmentation and insights in our marketing work–understanding the various groups that you’re speaking to, how they prefer to engage, and what they need to hear–before developing the most targeted strategy to reach them with your message. If governments’ primary role is to serve the people, why do they not take the same people-centric approach? Why don’t they engage designers, communication experts, and user-experience professionals to help make the legal language easier to understand, and processes simpler? We need to find ways to bring creative problem solvers together with lawmakers to come up with better ways to reach citizens of all kinds (even those without internet access), and we need to do it quickly.

And here’s a bonus: if we focus on making official information more accessible, we’ll also combat the problem with misinformation. Most people don’t have time to read four-page long memos of legal jargon. They just want to consume quick-hit facts and move on. But when our governments and other “credible” sources don’t give the user what they need, they will resort to other, easier to consume information that may or may not be accurate.

Communication design is only part of it

Design isn’t only about visuals and messaging: it’s also about how it works. The design of our cities and spaces affects the people who live there, as well as their wellbeing. In the early 1960s, activist and writer Jane Jacobs fought to keep New York City walkable and accessible for all people, while lawmakers and officials pushed for more highways. Jacobs fundamentally understood that a city is about humans, not buildings and that if we want safe cities, we need streets where people can walk, play, and work in the same spot. Her 1961 book, “The Death and Life of Great American Cities,” was a direct reaction to city planners’ attempts to overhaul neighborhoods to make way for more automobiles—an initiative that would have destroyed the SoHo and Little Italy neighborhoods if it wasn’t for Jacobs and her creative, and human-centric vision. Although not a trained designer, Jacobs understood the needs of the residents of her city, and she recognized the potential negative consequences of the officials’ plans for change. Non insignificantly, she was also brave enough to speak up.

Jacobs preserved her neighborhood by fighting against the lawmakers. But today, cities and countries are realizing the power of having creatives work with lawmakers instead. A few countries are even taking a big step to use the power of creativity to improve their cities.

The article: “Do countries need their own creative director?” published on Creative Review, features the Chief Creative Officer of Greece, Steve Vranakis, and the Chief Design Officer of Helsinki, Hanna Harris. Both Vranakis and Harris recently joined their respective governments to infuse creativity and design thinking into the somewhat antiquated and outdated governmental environments, and they both explain the opportunity creativity affords when it comes to solving big problems and improving the cities.

In the article, Vranakis, explains: “That approach to problem-solving, combined with the way we express it creatively and develop a narrative, is unique. People who operate in the creative industries do so in a certain way, and when you take that approach and apply it to government, it can yield interesting results.” His statement is followed by Harris explaining how as a designer: “You’re looking at an overall problem, challenge or situation, and seeing what’s at stake. There are different voices and people, and you then create methods to hear them and create something new that can take it forward to find a solution.”

The article highlights the creativity and it’s problem-solving ability. As creatives, we’re trained to look at problems as possibilities and find unconventional and interesting solutions that have not been tried before. And that is exactly what governments need, now more than ever.

Regardless of where you live, the government is big. And big, complex systems are hard to simplify. But just because it’s complex doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be rooted in humanity, employing design thinking and creative problem solving to find better ways to function. At this point in our history, when information is one of the most valuable resources we have to survive, a major shift in the way our government communicates isn’t a nice-to-have. Citizens deserve, and have the right, to access easy-to-understand information—and live in cities that are designed to help them live safer, healthier, better lives. But most of all, they need governments who are willing to try new, creative solutions to make a more sustainable society possible.